The Politics of IMF Crisis-Country Growth Projections

More on:

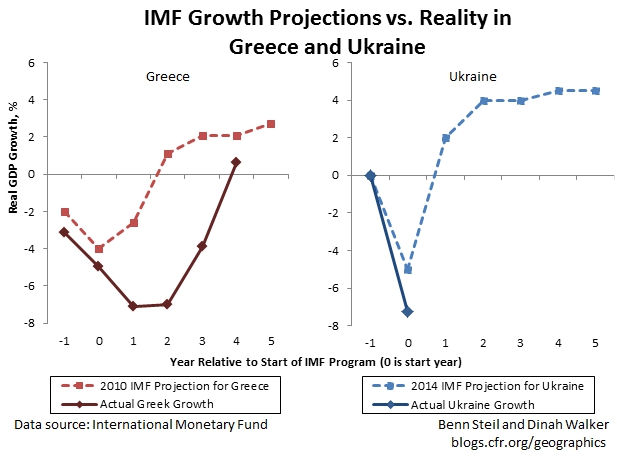

IMF GDP growth “projections” accompanying emergency lending programs are nothing of the sort; they are targets the level of which is necessarily set high enough to enable the interventions.

Take Greece. After committing to lending of €30 billion over 3 years in 2010, the Fund projected that the crisis-mired nation would return to growth by 2012. As shown in the left figure above, Greece’s economy actually plunged by 7% that year – the year it completed the world’s largest sovereign restructuring, covering €206 billion of bonds.

Take Ukraine. After committing to lending $17 billion over 2 years in April, the Fund projected that its civil/Russian war would magically end and its economy bloom – achieving 2% growth in 2015. Instead, its “adverse scenario” looks to be playing out according to script, with the economy on pace for a 7% decline. There is now a massive $15 billion gap between what has been pledged by the official sector (IMF, World Bank, European Union, and others) and what is actually needed to fund the government.

The point is not that the IMF is particularly incompetent or unlucky; few in the organization’s talented professional staff could be in the least surprised with how Greece and Ukraine have played out. The point is that the IMF’s growth projections for crisis-hit client countries are deliberately being pegged at levels high enough to overcome its own prohibition against lending to countries that lack sufficient funding to cover government spending over the coming 12 months.

This is a sound rule, intended to keep the Fund from getting sucked into the vortex of politics. Greece’s insolvency clearly required write-offs and gifts; more debt, which is all the Fund has to offer, was never going to resolve the problem. Ukraine requires at a minimum a cessation of hostilities. By all means, the EU, U.S., and other friendly nations should step in financially and otherwise to show solidarity, but such is not the proper role of the Fund. If it manages to avoid major losses on these interventions, it will only do so by having provided political cover for those who will – governments, such as those of Germany and the United States, which should have been up-front with their people about the likely cost and political purpose of their aid.

Financial Times: IMF Warns Ukraine Bailout at Risk of Collapse

Wall Street Journal: Ukraine Will Need More Bailout Funding, IMF’s Lagarde Says

IMF: Ukraine Request for a Stand-By Arrangement

IMF: Ex Post Evaluation of Greece's Exceptional Access

Follow Benn on Twitter: @BennSteil

Follow Geo-Graphics on Twitter: @CFR_GeoGraphics

Read about Benn’s latest award-winning book, The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order, which the Financial Times has called “a triumph of economic and diplomatic history.”

More on:

Online Store

Online Store